24 Jan 2025

Ah, graphics programming. For many, OpenGL has been the first step into this world. An easy to use, widely supported graphics API with decades of resources. However, modern demands in rendering have pushed OpenGL to its limits and Vulkan became a successor that offered more control. Maybe you’re here after just learning the basics of graphics programming with OpenGL and now want to give Vulkan a try or maybe you’re brave enough to step into graphics programming with Vulkan straight away. In this post, I’ll be talking about the basics of vulkan, the differences between it and OpenGL and some of my own experiences with Vulkan.

I started off with an engine that already had the basic structure for the renderer in place. The goal was to replace the OpenGL implementation with a Vulkan implementation. The OpenGL renderer I’m starting with has some basic features like: a GLFW window, instancing, PBR materials, lights (directional and point), shadow maps (only for directional lights), MSAA, and effects like fog and a vignette.

Even with libraries like vk-bootstrap to simplify setting up Vulkan it still requires a lot more setup than OpenGL. For instance you will need an instance, a physical device, a logical device, a swapchain, command pools, command buffers, and more. The instance is simply just the Vulkan API and does not need much configuring. Then you will need to find a physical device, this is your GPU. You can query for the device properties to select a GPU. Now that you have the physical device you need to create a logical device. The logical device specifies more specific information about what features you want to be using.

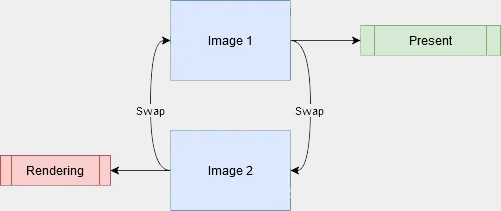

Now you will need the swap chain. The swap chain is basically a queue of images. While you might think that you would only need one image to render to and display, this would result into visible issues like screen tearing and stutters. We need to render to an image while we present another image. The swap chain manages this. You acquire an image from the swap chain, render to it, then hand it back for it to be presented.

Now you have the option to either use frame buffers and render passes or the dynamic rendering extension, which simplifies the API around rendering. I went with dynamic rendering. If you still want to use frame buffers and render passes I recommend reading the chapter about frame buffers in the Vulkan tutorial.

Next up is pipelines. More specifically graphics pipelines. It describes how Vulkan will render. For example the resolution it will render at but more importantly the shaders it will use. All of this needs to be configured before hand so you will most likely need multiple pipelines to render different types of objects.

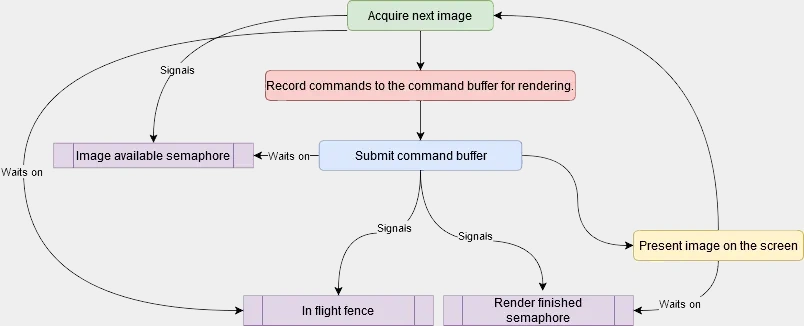

Something I didn’t mention earlier is that with the logical device you need to specify which queue families you would like to use. Queue families describe how a set of queues have similar purposes. Examples are: a graphics queue, compute queue, transfer queue, present queue. Vulkan talks to the GPU via commands. These commands need queues because Vulkan often performs operations in parallel. These commands are recorded to a command buffer which is created by a command pool which specifies what queue family it is. Then when you’re done recording the commands you submit it and let the GPU execute the commands. Once its finished it is presented to the screen.

Now for the actual rendering. After the command buffer begins recording you can start sending commands. First we will need to begin either the render pass or rendering depending on if you’re using dynamic rendering. I am using dynamic rendering so for me its begin rendering. This where you specify what image you will render to, what operation it should do when loading and storing the image, the clear value and the attachments. Now you can set the viewport and the scissor. A viewport defines the area of the image that will be rendered to. The scissor is the area of the image that is actually stored. This will basically always be from (0, 0) to (screenWidth, screenHeight). Now you can bind the graphics pipeline, vertex buffer and index buffer and send a draw command to render. A rendering loop would look something like this:

// wait for fences

// reset fences

// acquire next image

// reset command buffer

if (vkBeginCommandBuffer(commandBuffer, &commandBufferBeginInfo) != VK_SUCCESS)

{

Log::Critical("Failed to begin recording command buffer");

}

// colorAttachment

// depthStencilAttachment

VkRenderingInfoKHR renderingInfo{};

renderingInfo.sType = VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_RENDERING_INFO_KHR;

renderingInfo.renderArea = VkRect2D{{0, 0}, {m_screenWidth, m_screenHeight}};

renderingInfo.layerCount = 1;

renderingInfo.colorAttachmentCount = 1;

renderingInfo.pColorAttachments = &colorAttachment;

renderingInfo.pDepthAttachment = &depthStencilAttachment;

vkCmdBeginRendering(commandBuffer, &renderingInfo);

// Set viewport and scissor

vkCmdBindPipeline(commandBuffer, VK_PIPELINE_BIND_POINT_GRAPHICS, m_pipeline);

vkCmdBindDescriptorSets(commandBuffer,

VK_PIPELINE_BIND_POINT_GRAPHICS,

m_pipelineLayout,

0,

1,

&m_descriptorSet,

0,

nullptr);

PushConstant constant;

constant.pv = projection * view;

vkCmdPushConstants(commandBuffer,

m_pipelineLayout,

m_pushConstantStages,

0,

sizeof(PushConstant),

&constant);

VkDeviceSize offset = 0;

vkCmdBindVertexBuffers(commandBuffer, 0, 1, m_vertexBuffer, &offset);

vkCmdBindIndexBuffer(commandBuffer, m_indexBuffer, 0, VK_INDEX_TYPE_UINT32);

vkCmdDrawIndexed(commandBuffer, m_indexCount, 1, 0, 0, 0);

if (vkEndCommandBuffer(commandBuffer) != VK_SUCCESS)

{

Log::Critical("Failed to end recording command buffer");

}

// submit

// wait on render finished

// present

Sending over information to the shader like the transforms of the camera and the objects being rendered works a little bit differently than OpenGL. In Vulkan there are descriptors. A descriptor allows the shader to read from a buffer on the GPU. To use descriptors we need a descriptor set. Allocated by a descriptor pool the descriptor set stores a group of descriptors. Each descriptor set has a descriptor set layout which is given to the graphics pipeline. To use a descriptor set it needs to be bound before drawing just like you bind a vertex buffer. Just like OpenGL a command descriptor is the Uniform Buffer Object. New to Vulkan are push constants. Push constants are a small bit of data (usually 128 bytes) that can be sent to the shader without buffers or descriptors. They are useful for sending small per object data like an index.

Where in OpenGL you can simply just update a uniform at any point, in Vulkan you first need to setup a descriptor set. One of the problems I ran into was that descriptor sets can not be updated anymore after they’re bound during a frame. So when I was looping over my meshes to render them I tried to update the descriptor sets for each object. This resulted in it only working for the first object and a crap ton of validation layer errors telling me that the bound descriptor set has either been updated or destroyed. To solve this I uploaded all the object data to the GPU before the rendering through a descriptor set with a storage buffer. And then using the push constant to give the shader the objects index.

// simplified code

vkCmdBindPipeline();

PushConstant constant;

constant.pv = projection * view;

vkCmdPushConstants();

for ( const auto& mesh : meshes )

{

UpdateTransformBuffer(mesh);

vkUpdateDescriptorSets(); // Would only work for the first mesh

vkCmdBindDescriptorSets(); // Binds descriptor set

vkCmdBindVertexBuffers();

vkCmdBindIndexBuffer();

vkCmdDrawIndexed();

}

I mentioned validation layers just now. You might be wondering what those are. In OpenGL, error checking is done by the driver, which can lead to overhead and issues only being detected at runtime. Vulkan makes developers manage error checking themselves. Vulkan gives you validation layers. They are layers that go between Vulkan function calls to check for errors. This means by default Vulkan has no error checking which reduces driver overhead.

The coordinate system is also different in Vulkan from OpenGL. OpenGL is left handed while Vulkan is right handed. In OpenGL (0,0) is a the bottom left while in Vulkan it is at the top left. The Y axis in OpenGL points upwards but in Vulkan it points downwards. OpenGL’s depth range goes from -1 to 1 and Vulkan’s depth range goes from 0 to 1.

In OpenGL textures are mostly abstracted away. You call glTexImage2D and most of the memory allocations, format conversions, and bindings are done for you. In Vulkan you need to handle all of this yourself. First you need create an image, where you specify the format, size, and usage. Now you also need to allocate memory for this image. You can do this normally or using a library like Vulkan Memory Allocator (VMA). VMA abstracts complex parts of Vulkan’s memory management.

// Without VMA

VkBufferCreateInfo bufferCreateInfo = {};

bufferCreateInfo.sType = VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_BUFFER_CREATE_INFO;

bufferCreateInfo.size = size;

bufferCreateInfo.usage = usage; // e.g. VK_BUFFER_USAGE_VERTEX_BUFFER_BIT

bufferCreateInfo.sharingMode = VK_SHARING_MODE_EXCLUSIVE; // Used by a single queue

vkCreateBuffer(device, &bufferCreateInfo, nullptr, buffer);

VkMemoryRequirements memRequirements;

vkGetBufferMemoryRequirements(device, *buffer, &memRequirements);

VkMemoryAllocateInfo allocInfo = {};

allocInfo.sType = VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_MEMORY_ALLOCATE_INFO;

allocInfo.allocationSize = memRequirements.size;

allocInfo.memoryTypeIndex = findMemoryType(memRequirements.memoryTypeBits, properties); // Custom function

vkAllocateMemory(device, &allocInfo, nullptr, bufferMemory);

// With VMA

VkBufferCreateInfo bufferCreateInfo = {};

bufferCreateInfo.sType = VK_STRUCTURE_TYPE_BUFFER_CREATE_INFO;

bufferCreateInfo.size = size;

bufferCreateInfo.usage = usage; // e.g. VK_BUFFER_USAGE_VERTEX_BUFFER_BIT

bufferCreateInfo.sharingMode = VK_SHARING_MODE_EXCLUSIVE; // Used by a single queue

VmaAllocationCreateInfo allocCreateInfo = {};

allocCreateInfo.usage = memoryUsage; // e.g. VMA_MEMORY_USAGE_GPU_ONLY

vmaCreateBuffer(allocator, &bufferCreateInfo, &allocCreateInfo, buffer, allocation, nullptr);

In OpenGL the textures themselves contain sampler parameters like filtering and wrapping modes. In Vulkan samplers are completely separate objects. Vulkan also has image views. OpenGL doesn’t separate the texture object and its view. In Vulkan each image needs a view for it to be used. The image view for example specifies how many mip levels or layers the image has.

In OpenGL texture layouts and transitions are handled automatically. For example, when a texture is used as a render target and then as a shader input, OpenGL automatically transitions its state. Vulkan however, like usual, requires you to do this yourself. You use pipeline barriers to synchronize image transitions.

Unlike OpenGL where textures are bound, in Vulkan you need define all the images the shader will use in advance with descriptor sets.

Although Vulkan is undoubtedly more complex than OpenGL, I believe that Vulkan is currently the best option for a rendering API. Its main competitor, DirectX, only works on Windows and Xbox. If you already know some graphics programming/OpenGL, going through Vulkan should not be too difficult. If you still have an OpenGL renderer laying around I recommend trying to learn Vulkan by replacing that OpenGL code with Vulkan. While OpenGL will always be a great starting point for graphics programming, Vulkan offers more control and efficiency.